B.C. solitary confinement ruling has implications in Sask

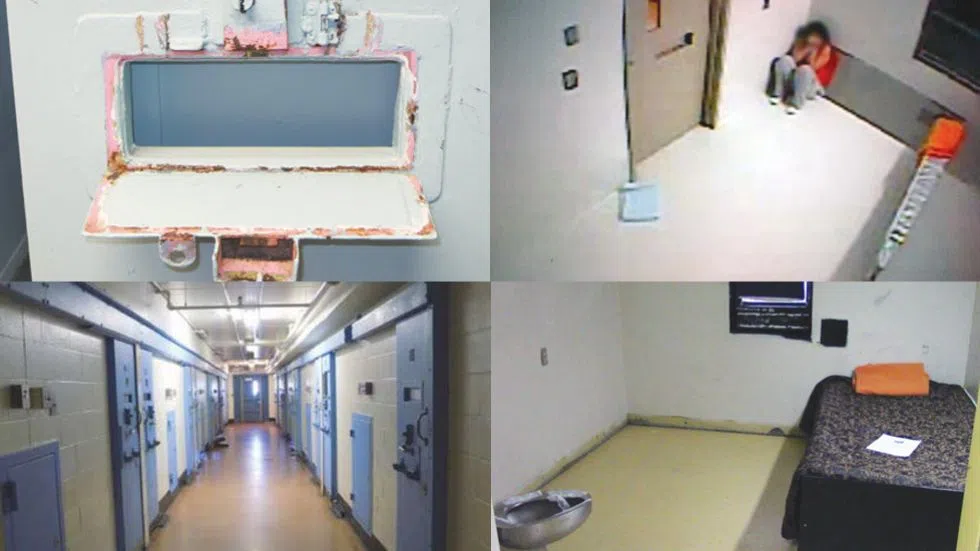

A recent decision by British Columbia’s highest court ruled indefinite solitary confinement unconstitutional could have a major effect on corrections in Saskatchewan, according to a leading advocate for inmates’ rights.

The B.C. Supreme Court ruled this week on a legal challenge put forward by the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association and the John Howard Society. In his decision, Justice Peter Leask said strict time limits must be placed on solitary confinement – officially referred to as “administrative segregation” – in order to avoid violating the constitutional rights of inmates. The practice creates risks for both the inmates and the general public, Leask found.

“Rather than prepare inmates for their return to the general population, prolonged placements in segregation have the opposite effect of making them more dangerous,” Leask wrote, “both within the institutions’ walls and in the community outside.”

On Wednesday Leask suspended his decision for 12 months to give the federal government time to draft new legislation setting strict time limits on segregation. The government has already introduced a bill that would set a limit of 21 days, with a reduction to 15 days after the new rules have been in place for 18 months, though it has not yet become law.