Study: Canadian teen mothers face increased risk of premature death, concerns raised in Saskatchewan

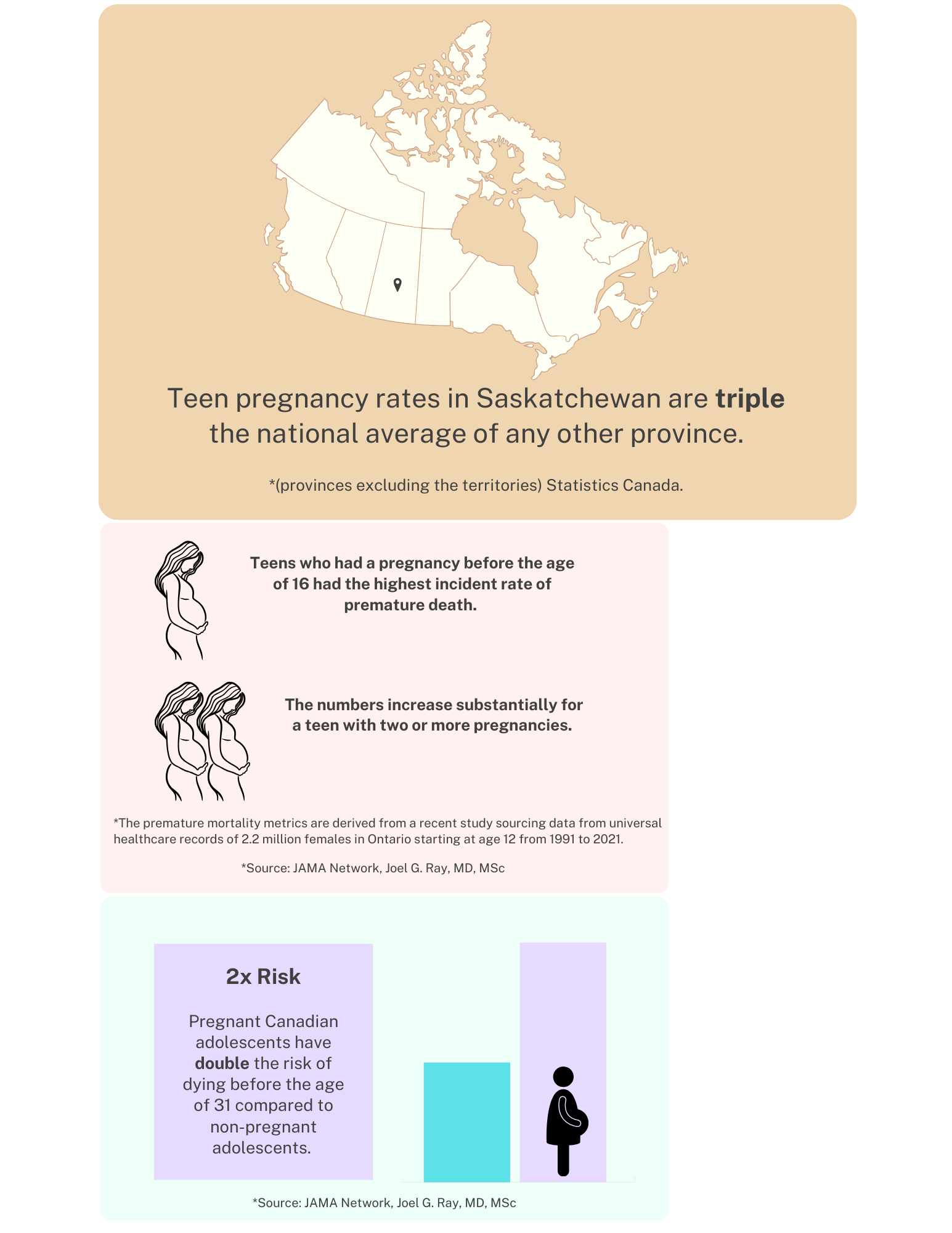

Pregnant Canadian teens face a new stark statistic: their risk of dying before age 31 is double that of non-pregnant adolescents. The issue draws attention to Saskatchewan, where teen pregnancy rates are triple the national average, and less mortality data is collected on postpartum mothers than any other province.

The premature mortality metrics are derived from a recent study sourcing data from universal healthcare records of 2.2 million females in Ontario starting at age 12 from 1991 to 2021.

The outcome revealed teens who had a pregnancy before age 16 had the highest incidence rate of premature death. The numbers increase substantially for a teen with two or more pregnancies.

Adjustments to the data were made for year of birth, pre-existing health conditions, income level and rurality.